The list of factors stated above as influencing quantity demanded may conveniently be summarized using notations. In other words, what we have said is that the amount of commodity a household is prepared to purchase is a function of the price of the good in question, the prices of all other goods, the household’s income and its tastes. This statement may be expressed in symbols by writing down the demand function:

Where is the quantity that the household demands of some commodity, labeled ‘commodity n’, where is the price of this commodity, where, is a short hand notation for the prices of all other commodities, where Y is the household’s income and T the tastes of the members of the household.

This is quite a complicated functional relationship, and we shall succeed in developing a simple theory of demand or price if we consider what happens to the quantity demanded when these things—prices, income and tastes—all change at once. This may pose some complexity, but the way to get around it is to assume that all the right hand variables except price is held constant and only price is allowed to vary. We then allow some other term, say income (Y), to vary and consider how ceteris paris paribus, quantity demanded varies as income varies. We now consider each of the variables one at a time and explain how it affects demand.

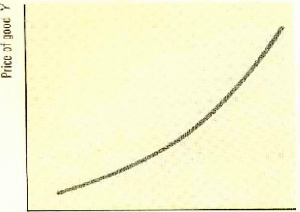

The curve slopes upward, indicating that as the price of a substitute falls, the demand for the good falls. Example of substitute goods includes; butter and margarine, public transport and private cars.

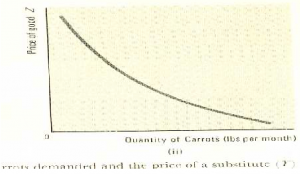

If a fall in the price one good raises the demand for another good, the two goods are said to be complements. In this case, when the price of one good falls, more of that good is consumed and also more of these goods that are complementary to it. This relation will obtain between goods that tend to be consumed together, goods such as motorcars and petrol, bread and butter. This is illustrated in the figure below

The curve slopes downward, indicating that when the price of a complement falls there is a rise in the quantity demanded.

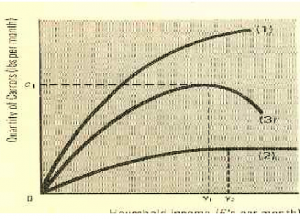

Curve 1 illustrates the case in which a rise in income brings about a rise in purchases at all levels of income. Curve 2 illustrates a case in which purchases rise with income up to a certain point Y2 and then remain unchanged as income varies above that amount. Curve 3 illustrates the case in which purchases first rise with income up a certain level Y1 where purchases are C1, but then fall as income goes beyond that level: the good becomes inferior at incomes higher than Y1.